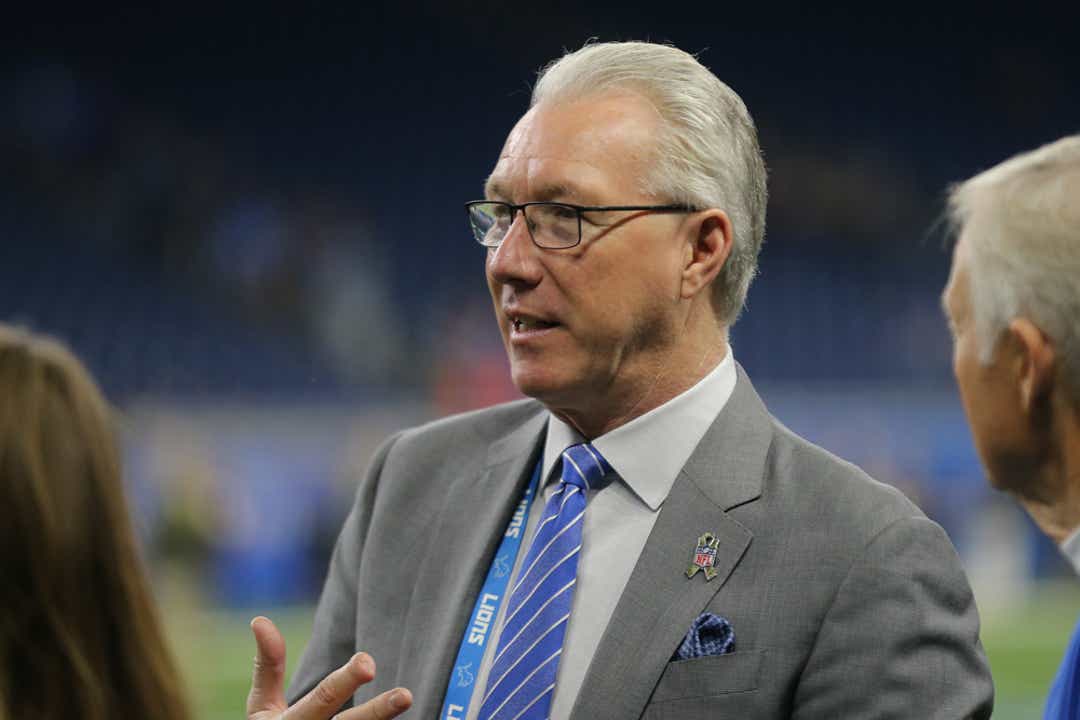

When Rod Wood and his wife, Susan, went out for a recent dinner at the Renaissance Center, the Detroit Lions president got a glimpse of what the not-too-distant future might look like when it comes to attending NFL games.

Everyone who enters the 73-story building overlooking the Detroit River must answer three questions about their health and recent travels, then proceed down a hallway for a thermal body temperature scan.

If a visitor’s temperature registers below that day’s threshold, they receive a yellow “scanned” sticker and are allowed access to the building.

[ The Free Press has started a digital subscription model. Here’s how you can gain access to our most exclusive sports content. ]

Masks are required and social distancing is adhered to at all times.

For Wood, going to dinner felt like “I was going to a hospital or something.” But given the way the coronavirus pandemic has upended life for the major American sports, it’s possible that experience becomes standard in stadiums, arenas and other venues built to hold tens of thousands of fans.

In the years that followed the 9/11 attacks, the NFL and other professional sports leagues put in place security measures that at first seemed heavy-handed but now are standard: Buffer zones around ballparks, 24-hour live security feeds, walk-through metal detectors, hand wands and clear bags are some of today’s protocols that did not exist in most sports venues a generation ago.

“I think there can be some aspects of that, that become permanent like the 9/11 security measures that you talked about,” Wood said. “I would say it’ll depend on a couple things. One, what does it mean to have the virus truly under control? Does it mean it’s here, but people are not worried about dying from it, but you still don’t want to get it? So some of those things might linger forever, or for a long time.

“And then I think the other thing it’ll just depend on is, what people feel makes them feel safe the most, and, ‘I’m not going to go to that place because they don’t have those kind of measures, this place does.’ And I think the consumer probably will dictate a lot of that stuff. The 9/11 measures were more dictated by the government to protect the country and people. I think in this case, it might be as much directed by the consumers, that I’m not going to go to a place that’s not keeping their facility clean and protecting me and their employees, and it’s appropriate to wear a mask and wearing gloves and all those things that are common now.”

The NFL is set to kick off its 101st season Thursday night when the defending Super Bowl champion Kansas City Chiefs host the Houston Texans at Arrowhead Stadium in front of roughly 17,000 fans, or 22% of the stadium’s capacity.

The Lions open the regular season Sunday against the Chicago Bears in what will be an otherwise empty stadium. Restrictions in the state of Michigan currently limit sports venues to 25% capacity or 250 people, whichever is smaller. Ford Field normally holds 65,000 fans.

[ Lions still hope to have fans at Ford Field as soon as Nov. 1 vs. Colts ]

Football at Michigan, Michigan State and across the Big Ten remains on hold, despite protests from players, while other colleges across the country try and navigate the slippery slope of playing during a pandemic.

COVID-19 has forced the NBA and NHL to finish their once-halted seasons in bubble environments. And the Detroit Tigers are vying for their first playoff berth since 2014 while playing in empty stadiums across the Midwest.

Sports have not changed much between the lines because of the pandemic — and likely won’t going forward. But everything else about them, from the economics of the games to the spectator experience, is barreling towards an uncertain future.

“Our sports bring people together,” said Johnny Smith, a professor of sports history at Georgia Tech. “They are community gathering sites, and they also provide a sense of distraction from the outside world in many ways. Of course, today we see that’s not the case. Sports can’t provide a distraction because there’s no escaping the virus. The virus is shaping the sports world.”

Learning from the past

The last time a virus the magnitude of COVID-19 hit America was more than 100 years ago: the influenza pandemic of 1918.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that pandemic infected an estimated 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population, and killed some 675,000 in the United States alone.

COVID-19 has affected an estimated 27.6 million worldwide and killed 190,763 nationally, according to Johns Hopkins University.

“If you read the newspaper accounts from 1918 you’d swear you were reading today’s New York Times,” said pro football historian Joe Horrigan. “It’s unbelievable. They’re talking about closing schools and wearing masks and funeral homes being loaded up with bodies that they couldn’t handle. It’s very, very similar.”

The influenza pandemic of 1918, like this year’s COVID-19 outbreak, coincided with a time of social unrest. Government misinformation, plus soldiers traveling home from and overseas to World War I, contributed to its spread. And as with this year’s pandemic, the 1918 plague caused massive disruptions to the sports world.

The World Series in 1918 was moved from October to September, though Smith said that was largely due to the war. But when the second, deadliest wave of the pandemic hit, from September to December of 1918, it shortened the college football season — Michigan claims a national championship with a 5-0 record that year — and canceled the most prominent pro football league — the Ohio League — entirely.

Horrigan said pro football returned largely to its pre-pandemic ways in 1919, after the government lifted bans on large gatherings. People stopped wearing masks to sporting events, and football was so popular that in 1920 the NFL was formed.

“The ’20s is really this era of a stadium boom for college football,” Smith said. “So many stadiums now are War Memorial Stadium or Veterans Memorial Stadium, they’re all over the country. And these were massive concrete stadiums that still exist today, and I think the point is that there was, in the words of President (Warren) Harding at the time, the Americans wanted to return to a sense of normalcy. He meant the word normality, but the same is true today that our sports are created in part to bring people together and so I think ultimately that people want to have that interaction again.”

Sports, of course, is a much bigger business now than it was 100 years ago, and the financial incentives to keep it flourishing are immense.

So while everyone is yearning for a return to normal, from youth soccer leagues to high school football players to the college and pro teams whose seasons currently hang in the balance, Smith, Horrigan and others say it’s better to look at how sports changed after more modern events to find a blueprint for the road ahead.

“The NFL has been terrific in their response to the aftermath of things like in New Orleans with (Hurricane) Katrina and 9/11 and World War II,” Horrigan said. “They were very proactive in maintaining the sport through the very, very challenging times, so I don’t see why it would be any different this time. I think they will be proactive to make sure that there’s the best practices model again.”

‘Remnants of COVID’

Of all the professional sports, the NFL is perhaps uniquely suited to withstand the coronavirus pandemic.

The virus first surged nationally in March, during the league’s offseason, so while the NBA and NHL were forced to halt their regular seasons, and Major League Baseball had to pause spring training, the NFL was able to take a wait-and-see approach with its games.

Teams that don’t host fans this year still are projected to lose, conservatively, $70 million in gate receipts, according to CBS. But the NFL derives the vast majority of its revenue from massive media rights deals — every team received $296 million in national revenue this year — and teams share some local revenue, with the salary cap adjusting annually based on those numbers.

Add in new gambling revenue streams and the fact that the league spans both the back-to-school and holiday shopping seasons that are so important to advertisers, and Marc Ganis, president of Sportscorp, a leading sports business consulting firm, said he has no doubt the NFL will continue to flourish post-pandemic.

“The pandemic has demonstrated that the NFL is like one of the well-capitalized, great-balance-sheet, must-have companies, must-have services companies, like Amazon and Apple,” Ganis said. Amazon’s market capitalization has grown by more than 75% this year, and Apple’s by more than 50%, despite the pandemic. “It’s at that level. There are many people and businesses that are eager, waiting with baited breath, for the NFL to come back. … So the NFL will get stronger, just like Amazon and Apple got stronger during the pandemic.”

As strong fiscally as the NFL should remain, there are significant changes and potential pitfalls that await both it and other leagues.

Collegiately, the pandemic has further exposed a business model built on the backs of unpaid laborers, and with revenue streams disrupted in the money-generating sports of NCAA football and basketball, universities have been forced to slash budgets and, in many cases, eliminate non-revenue teams.

For subscribers: Michigan football programs brace for ‘major impact’ of new NCAA rule

Smith said he fears for the future of the Olympics after this summer’s Tokyo Games were postponed until 2021. Japan’s Olympic minister recently said the games will go forward next year “at any cost,” but Smith said the pandemic could make nations interested in bidding on future games more wary of investing in the infrastructure needed to pull them off.

NBA and NHL arenas may need to be permanently reconfigured to move fans farther away from players and playing surfaces. And depending on how long fears over the virus (or future pandemics) last, NFL stadiums may look different in their next iteration, with more open space and smaller seating capacities.

“If you think about it, in the ’70s and into the ’80s, cities and communities were being asked to build 80,000-seat stadiums,” Horrigan said. “Now, that’s not even on board. First of all, the league is not asking communities to pay anymore, but they’re building 60,000-seat stadiums that are expandable for a Super Bowl if they’re interested. The butts in seats aren’t as important as TV and fantasy football, and now unfortunately probably gambling for revenue. So the live arena scenarios could change.”

Live arena scenarios could change for other reasons, too.

Ganis, who has consulted with NFL teams on the construction of stadiums in the past, said he foresees more open-air stadiums or retractable-roof venues in the future, where touchless amenities in common areas and deck spacing abound. Ingress and egress procedures will be different, and there’s a chance that habits formed during the pandemic, when families invested in summer homes, swimming pools and home reconstruction projects, will keep some people from stadiums altogether.

“I don’t see the virus as reducing the interest in sports,” he said. “There are other societal factors that I’m a little more concerned about. And some are remnants of COVID. People have sort of found they can do things, spend more time with their families, more time at home, and the importance of having a second home if they live in cities. So we may see some of the things that people found to do when we had no sports, and some percentage of the population will prioritize those things for at least some of their sports time and enjoyment.”

‘It could happen again’

Wood, who has often talked of enhancing the in-stadium experience during his five years as Lions president, said he has considered those possibilities, too, and he pointed to a recent Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis study to explain the uncertainty ahead.

The study suggested that effects from the pandemic could linger in the economy for up to 70 years.

“They kind of likened it … to the depression and you talk to anybody who went through the depression, it still is on their mind today,” Wood said. “They still think about too much debt, I might lose my house. And I don’t want to have too much money in the bank because the banks go out of business. You still hear that if you know anybody that lived through the depression, or were a child during the depression, they remember their dad losing his job and being on the soup line.

“Once you live through that, you think it can happen again. So I think people that have lived through this, for now — and maybe for 70 years — will be thinking this can happen again. And where the economic effect could last that long was the thought of, put somebody in my seat or somebody running another company, when you’re doing your business planning you’re probably in the back of your mind always going to have, ‘Well, what are we going to do if we have another pandemic?’ ”

The Lions and most teams go through extensive disaster recovery plans to prepare for unlikely scenarios that leave their buildings unavailable or otherwise impact business.

Wood said most executives do those “because you feel like you have to, but you’re not really ever thinking you’re going to have to do that.”

And now?

“Now people are saying, ‘That’s real. It happened. And it could happen again,’ ” he said.

For as extraordinary as the past six months have been, the NFL is planning for a normal 16-game season. There are contingencies in place if an outbreak occurs, but as of Wednesday just three players were on the league’s reserve/COVID-19 list.

Five NFL teams will have fans in their home stadiums to open the year, and while the Lions are not one of them, Wood remains hopeful that will change come Nov. 1.

If fans are allowed, they won’t be greeted by thermal body scanners yet, but they will see a host of other changes to the game day experience.

“We’re probably working off of a 20, 25% maximum capacity, because regardless of what the states allow, the league’s mandate is you’re going to have the lesser of your state or the CDC guidelines,” Wood said. “We’ve made a bunch of models of different pods, of groups of two for families, groups of four for families, groups of six for families, and then how many seats need to be blocked off between that pod and the next pod. And then you got the suites, and how many seats are you going to block off in the suites so that you don’t have people in one suite sitting next to the person in the next.”

Fans will be required to wear masks at all NFL stadiums this fall, and Ford Field likely will have assigned entry times and gates. Tickets will be paperless, concessions will be cashless, and safety measures have been installed throughout the building including touchless faucets in restrooms and Plexiglas barriers at vending areas.

Unlike past years, no cheerleaders, mascots or elaborate pre-game introductions are allowed on the field, and sponsored events during timeouts and halftime entertainment acts are off limits.

The football should look the same as always, but the NFL — like all professional sports as we’ve come to know them — will be different.

“I’ve now kind of decided that we’re going to have some seminal, never-going-to-happen-again event every 10 years,” Wood said. “You had 9/11 in ’01 and then you had the financial crisis in ‘08-09 and now you’ve had this in ’20, so basically three once-in-a-lifetime events have occurred in the last 20 years. So I think if you’ve experienced that enough you’re going to believe that there’s another one of these once-in-a-lifetime events — maybe it’s not a pandemic, it might be something completely different, in the next five to 10 years.”

Contact Dave Birkett at dbirkett@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @davebirkett. The Free Press has started a new digital subscription model. Here’s how you can gain access to our most exclusive Lions content.